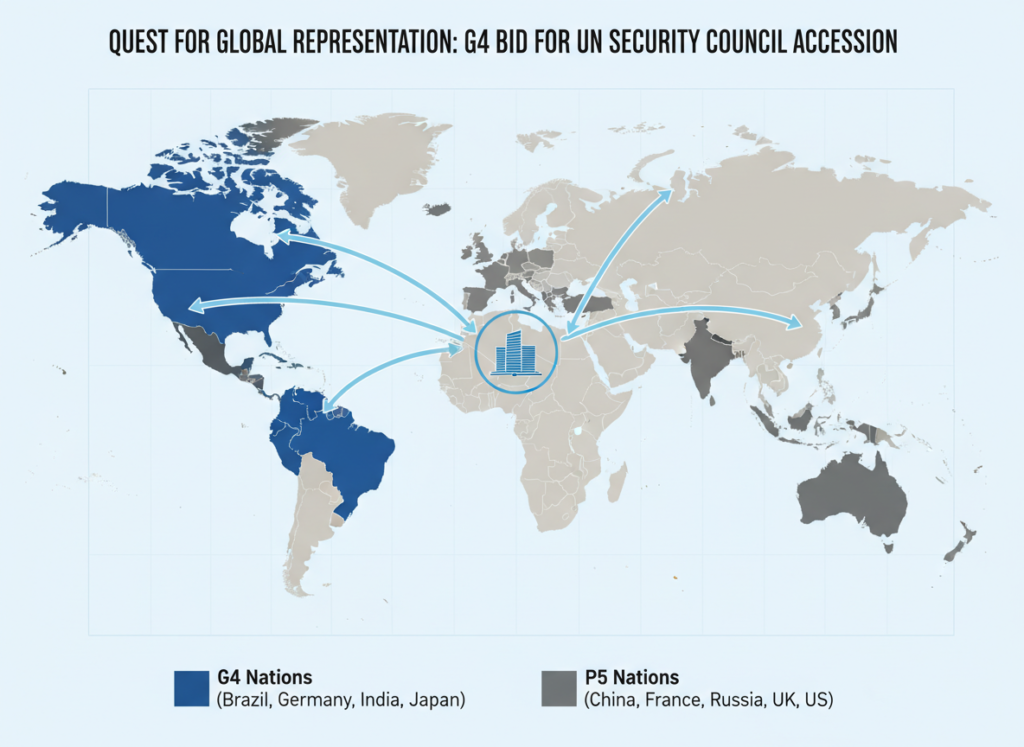

As the United Nations marches past its 80th anniversary, the call for structural reform has transformed from a diplomatic nicety into an urgent geopolitical necessity. At the heart of this debate lies the G4 Model for UNSC Expansion, a comprehensive proposal championed by Brazil, Germany, India, and Japan. These four nations—economic heavyweights and major contributors to global peace—argue that the Security Council’s 1945 architecture is dangerously obsolete.

In January 2026, the G4 nations renewed their vigorous push for text-based negotiations, warning that further delay risks the credibility of the entire multilateral system. This article provides an analytical deep dive into the G4 proposal, its strategic rationale, and the formidable obstacles it faces from rival coalitions like Uniting for Consensus.

Decoding the G4 Proposal: Structure and Membership

The G4 Model is not merely a request for seats; it is a structural overhaul designed to reflect contemporary geopolitical realities. The current Council comprises five permanent members (P5) and ten non-permanent members. The G4 argues this leaves vast regions of the world, particularly Africa and Latin America, without a permanent voice at the high table.

Proposed Composition

The core of the G4 proposal advocates for expanding the Security Council from 15 to 25 or 26 members. This expansion is targeted at both categories of membership:

- 6 New Permanent Seats: Two for African states, two for Asia-Pacific states, one for Latin American and Caribbean states, and one for Western European and Other states.

- 4-5 New Non-Permanent Seats: To ensure broader rotation and representation for smaller states, including Small Island Developing States (SIDS).

Under this model, the G4 nations support each other’s bids for permanent membership while crucially backing the Common African Position (Ezulwini Consensus) for two permanent seats for Africa.

The Strategic Rationale: Why These Four?

The argument for the G4 nations ascending to permanent status is rooted in their material and political contributions to the UN system. They are not merely asking for representation; they are formalizing their role as primary stakeholders in global stability.

1. Economic and Demographic Weight

Combined, the G4 nations represent a massive slice of the global economy and population. India, now the world’s most populous nation, and Brazil, the demographic and economic giant of South America, represent the Global South’s rise. Meanwhile, Germany and Japan remain top-tier funders of the UN budget. Continuing to exclude the world’s third and fourth-largest economies (Japan and Germany) from permanent decision-making undermines the Council’s operational legitimacy.

2. Contributions to Peacekeeping and Development

India and Brazil have historically been among the largest contributors of troops to UN peacekeeping missions. Germany and Japan are critical pillars of international development aid and humanitarian relief. The G4 argument is simple: those who shoulder the burden of maintaining global peace should have a decisive say in how that peace is managed.

The “Veto” Conundrum and Tactical Flexibility

One of the most contentious aspects of UNSC reform is the veto power held by the P5 (US, UK, France, Russia, China). The G4 has displayed significant diplomatic flexibility here.

While maintaining the principle that new permanent members should have the same responsibilities and obligations as current ones, the G4 has proposed to forgo the use of the veto for an initial period (often suggested as 15 years) until a comprehensive review is conducted. This pragmatic concession is designed to soften opposition from the P5, who are wary of diluting their exclusive power, and to reassure smaller states that an expanded council won’t become gridlocked.

However, this stance creates friction with the African Union’s Ezulwini Consensus, which demands new permanent seats with full veto power immediately. Bridging this gap remains a critical diplomatic hurdle for the G4.

The Opposition: Uniting for Consensus (UfC)

The primary organized opposition to the G4 model comes from the Uniting for Consensus (UfC) group, nicknamed the “Coffee Club.” Led by Italy, and including nations like Pakistan, Mexico, Argentina, and South Korea, the UfC opposes the creation of any new permanent seats.

The UfC Argument

The UfC argues that adding new permanent members creates a new tier of privileged nations, further “oligarchizing” the UN. Their counter-proposal focuses on:

- Expanding only the non-permanent category.

- Creating longer-term renewable seats to allow major regional powers to serve more frequently without granting them permanent status.

- Democratizing the Council by ensuring all members remain accountable to the General Assembly through periodic elections.

For detailed analysis on these opposing coalition dynamics, the Global Policy Forum offers extensive archives on the history of these negotiations.

Recent Developments: The 2026 Push

The diplomatic landscape has shifted significantly between 2024 and early 2026. The Summit of the Future in September 2024 produced a “Pact for the Future” that explicitly called for urgent UNSC reform to correct historical injustices—a clear nod to Africa and the G4’s grievances.

In January 2026, the G4 Foreign Ministers issued a joint statement emphasizing that the Intergovernmental Negotiations (IGN) must move to text-based negotiations. For decades, discussions have been circular because they were not based on a single draft document. The G4’s insistence on a negotiating text is a strategy to force nations to go on record with specific amendments rather than hiding behind vague rhetorical opposition.

Furthermore, shifting stances from P5 members—including the United States explicitly signaling openness to expansion—have energized the G4’s campaign. However, China’s alignment with the UfC position and Russia’s cautious approach continue to complicate the path to the required two-thirds General Assembly vote.

Conclusion: A Question of Legitimacy

The G4 Model for UNSC expansion represents the most viable, detailed pathway to a reformed Security Council. While critics in the UfC fear a new hierarchy, the G4 counter-argues that the current hierarchy is frozen in 1945 and is rapidly losing relevance. Without integrating the major powers of the 21st century—and correcting the historical exclusion of Africa and Latin America—the Security Council risks becoming a relic.

For students of international relations and policymakers alike, the success or failure of the G4 bid will be a defining case study in the capacity of global institutions to adapt. As the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace has noted in recent analyses, the “middle power moment” is here; the only question is whether the UN structure can expand to accommodate it.